Frameline Celebrates Carol, Todd Haynes, and Queer Resilience

On December 21, 2025, hundreds of people gathered outside San Francisco's Toni Rembe Theatre, waiting in line to participate in a holiday ritual that has become a cornerstone of the queer calendar. The crowd was dressed in a chaotic mix of aesthetics: some were in character for the film, adorned in sharp silhouettes of the 1950s, while others came in a storm of colors embodying the spirit of a Frameline screening. We were there for Frameline’s "Carol Day," an evening dedicated to celebrating the 2015 film Carol. We were also there for the inauguration of the Queer Lens Award for Filmmaking, an honor recognizing filmmakers who refuse to let the outsider's gaze be anything less than grand.

But just as the evening was about to start, a technical failure shut down the projector. In any other setting, this would have triggered a mass exodus, but here the energy remained charged. There was a tangible bond among the audience; everyone was there to celebrate a film whose power transcended its celluloid housing. They did not care if they were going to watch Carol or not. They were there to experience Carol, which did not require a DCP (Digital Cinema Package) to be felt. We were there to be part of a community celebrating a film that has spent a decade teaching us how to navigate the very repression currently resurfacing in the world outside.

Frameline has spent nearly half a century championing unapologetic queerness through film, and the Queer Lens Award is the natural evolution of that vision. This award is dedicated to recognizing a filmmaker who brings a singular vision that makes an indelible impact on the art form. Todd Haynes was the inevitable first recipient of this award. His career is a prolific refusal to let queer stories be small, simple, or stripped of their cinematic grandeur.

Photo Courtesy of Tommy Lau - Instagram (@tommysees)

Director Todd Haynes on repression and resilience:

Earlier that evening, I spoke with Haynes. He talked in a gravelly baritone, weighed down by a mild cold that added extra weight to his words. I started the conversation by asking him about reconciling with Carol’s power now that it has taken its place in the hall of fame of queer classics. "Of course, I couldn't have had those kinds of expectations or projections," Haynes told me. "But I was very aware that we were adapting a novel with its own remarkable history. We just wanted to do justice to that."

To adapt The Price of Salt (1952) means one would have to grapple with a genealogy of queer survival that predates the modern movement as we know it. Patricia Highsmith published the novel under a pseudonym. This was the same year the American Psychiatric Association classified homosexuality as mental illness. The lesbian fiction that preceded it operated under a regime where that vision felt impossible. For lesbian romances, death, institutionalization, or conversion were the only available conclusions. Highsmith's intervention was radical because it was the first of its kind where the lovers were allowed to survive and exist openly. Her heroines walk towards each other at the novel's conclusion rather than away.

Haynes spoke of the film's global footprint, a reach he admits is overwhelming to process. "There have been experiences that I've heard from women around the world, whose testimonies were collected after they saw Carol. In all kinds of different places, and countries, and regimes that are much more restricted regarding gay life. That is something that's very hard to hold in your head. But it's incredibly meaningful." This is simply just another testament to Carol’s power, a strong reminder of how art can function as a survival kit in societies where the mere act of yearning is a revolutionary transgression.

Photo Courtesy of Barak Shrama - Instagram (@barakshramaphotography)

Carol takes place in a time of repression. By contrast, when it was released in 2015, it was met with a rapturous applause at Cannes. It was at a time when it felt like the arc of history was trending towards justice and empowerment for all. As we reflect on the current moment, it often feels (by some definitions of progress) that we are regressing closer to the world in Carol than we were in 2015. One decade later, it feels as if we are living within the film rather than outside it. Haynes’ assessment of our current political moment was unflinching:

"It can't be overstated how much we've retreated from so many hard-fought battles. The new permission granted to bigotry, racist language, misogyny, continues to absolutely astonish and startle so many of us."

Yet he finds resilience in the counter-narrative. "What I do feel is that the country is way more informed and resilient than at times of disparity I’ve felt in the past. I think we're going to look back on this period with incredible shame."

Carol inspires us to push past repression and deny silencing our truest selves. When I asked what parts of himself he inserted into the film, Haynes spoke about the universal language of intimacy. "We all recognize both sides of the power dynamic when you're in love. You feel completely outside of the world. You're shut out. And you're both fierce and incredibly vulnerable at the same time."

To be "fierce and incredibly vulnerable" is part of what makes Carol and Haynes’ broader catalogue endure with such a lasting legacy, one that feels as if the work is sentient. It speaks for itself, championing interiority while the exterior world demands erasure.

Photo Courtesy of Barak Shrama - Instagram (@barakshramaphotography)

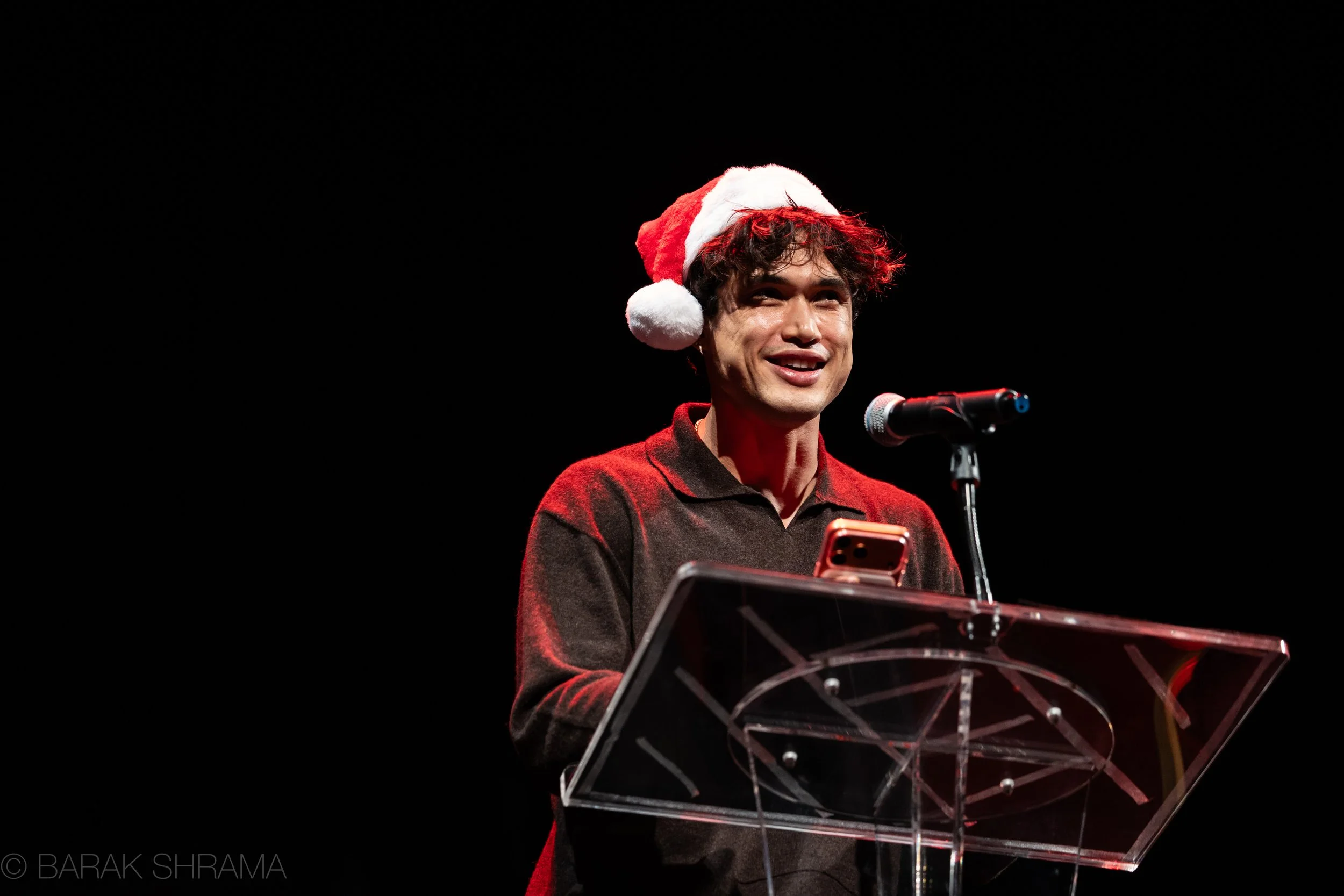

Actor Charles Melton on Carol’s universality:

I spoke with Charles Melton, who was there to present Haynes with the award. Melton, who delivered an extremely vulnerable performance under Haynes' direction in May December (2023), spoke with an immediate and unguarded enthusiasm for Carol. “It’s so good. It is so so beautiful.”

I pressed him a little bit more on why he felt so drawn to the film – a story ostensibly about two women falling in love in the 1950s. His answer gave serious credence to the power of the film:

"This film transcends any sort of construct; we all understand oppression. Any human who understands any sort of repressed feeling, or wanting to live their truth, relates to this. It's one of those films where you're discovering yourself for the first time when you watch it. Todd's not telling you how to feel, but you're experiencing in this luscious buffet of visual art and performance and writing, your own self."

Melton did not arrive at the film through the vectors of identity that might seem to predetermine its audience. His love for Carol is just another reminder of the porousness of the work, especially in its capacity to envelop anyone capable of recognizing constrained desire.

Photo Courtesy of Tommy Lau - Instagram (@tommysees)

Carol beyond the screen:

As we waited for the event to kick off, I wanted to discuss the film with audience members. Dominique O'Neil spoke to the "queer yearning"at the heart of the film. "Carol encapsulates a queer yearning that is so rarely captured in film in its nuance and in its weight," they said. "For a lot of millennial and older generations, we have coming out stories that are not easy. There is something resonant about finding a kindred spirit in times of repression, in times of not fully knowing if you can be out or not."

Ruha Devanesan, another audience member, connects to the film through her own history. She was raised in Singapore where the social dynamics that were depicted in the film felt closer to reality rather than period reconstruction:

Growing up, I wasn't out for a long time - until I was 21. My first loves were always unrequited. The tension in this movie is very familiar to me - it's how I came into my romantic self. The social dynamics in this film are actually very similar to Singapore in the 90s and 2000s. Our rights as a community ebb and flow, depending on who's in power. It's essential to remember that nothing is permanent. Things feel really hard now. The oppression is real and horrific. Don't lose hope. We can get out of this.”

The state of the world is never permanent, freedom ebbs and flows. The only thing that is truly permanent is the impact of art and the strength that it fills us with.

With no film to show, the evening turned into a celebration of Carol and all it represents. From Peaches Christ’s high glamor chaotic performance, Charles Melton’s sincere speech, and a moderated Q&A featuring Todd Haynes and his long-time producer Christine Vachon, the air stayed electric. I can go on about how powerful it felt, but I think that power is best captured in this reflection from Frameline’s Executive Director, Allegra Madsen:

"This year, I want to think of Carol Aird as an incredibly brave and vulnerable figure. At the end of the film, there is always discussion as to whether it has a happy ending. I see Carol as a figure with a profound understanding of the world she exists in. She is in that world—it is inescapable—but it does not have to be in her. It does not have to define who she is. She has the power to do that."

We sat in the dark, cheered for a film we couldn’t see. Carol was not there, but she was alive. Technical difficulties didn’t ruin the night. They just helped us remember why we were there. While we often think of "infrastructure" as the technical apparatus of cinema (the glass of a projector lens that, on this night, proved unchangeable), the true architecture of Haynes’ legacy is his film's ability to live inside those who watch them.