Interview with Giovanna Ferrari, Director of Éiru

Giovanna Ferrari remembers being considered a strange child with adults making fun of her behavior and interests. "I remember that it happened a lot, and sometimes it really hurt," she says. "I think I wanted to have a character that adults make fun of, but she's actually right. She's the one who's right."

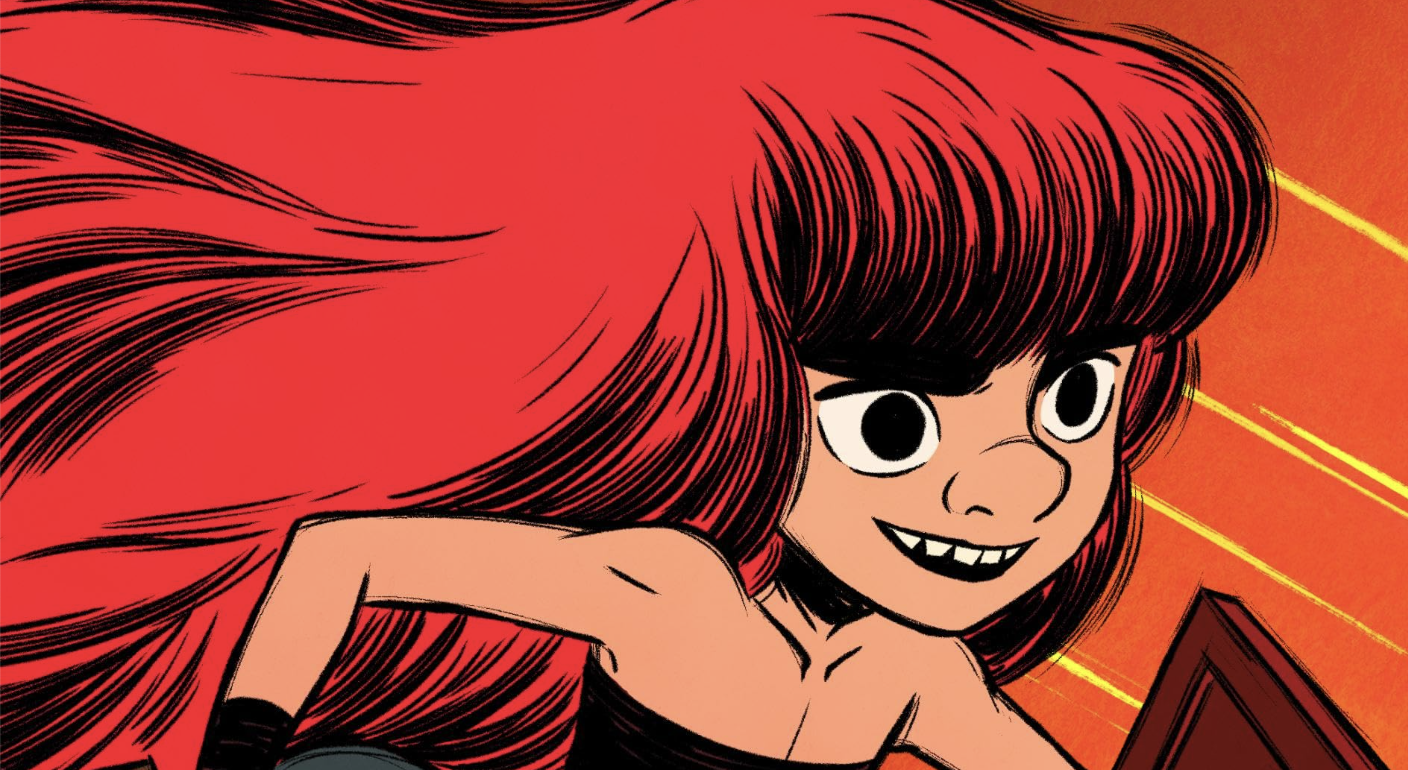

Éiru is a thirteen-minute animated film about a girl who is too small to be taken seriously by her clan of Iron Age warriors. When the village well runs dry, she is the only one who can fit into the earth to find out why. The premise sounds like a children's fable, but Ferrari, who spent two decades at Cartoon Saloon working on films like Song of the Sea, The Breadwinner, and Wolfwalkers, uses it to ask a harder question: Why do we keep dismissing the people who see what we can’t?

Ferrari rarely brings up this connection to her own isolation in interviews. It is a piece of her history she usually keeps to herself. This feeling of being an outsider has followed her through a life defined by movement. As an Italian expat who raised her daughter while moving across various European countries, she is familiar with the friction of being "the other." She remembers leaving Italy in her twenties and seeing a bizarre contradiction in the people she left behind. The same people who celebrated her ambition in going away were often the ones who resented the arrival of others. "I still remember how the people celebrating my ambition were also the same people who were unhappy that other people would come to Italy and work there," she says. "I couldn’t understand how those two things could coexist in the same person."

That contradiction is built into the clan structures of the film. The warriors are so preoccupied with opposition—Flame against Stone against Tree—that they fail to notice the destruction of the earth beneath them. Ferrari spent years in a similar state of interrogation within the animation industry. As a young woman in rooms historically dominated by men, she frequently wondered if her own identity was a liability to her success. "For a long time, I was questioning myself and how I should behave. Was I supposed to try to be like them? Being myself as a girl was not necessarily something that was accepted. In the best case scenario, I was made fun of. There were other situations that were very uncomfortable, so what could I do with myself?"

She eventually realized there was no clean answer to that struggle. The only viable response was a relentless commitment to the quest itself. "The commitment, not giving up, and continuing your quest is the answer, I guess. One of the answers."

Everything changed when she had her daughter. Raising a child forced Ferrari to confront the fact that children are not just smaller versions of humans, but sensory beings with a potency of thought that equals adults. "The moment that I had her, I started to realize that children are humans. They are like adults. Their ideas, their thoughts, and their opinions are really important, and I really don’t understand how people can dismiss them," she explains. She believes that children reveal things about the adults around them, and that the goal of parenting is to create a person who is able to tell you that you are wrong. "And you should listen when they do."

This belief leads Ferrari towards a meditation on the nature of time. She believes that children are not bound by the limits of adulthood, nor are they corrupted by the same limitations that we face. She even suggests that children’s innocence allows them to break the limits of time because they have not yet been taught to live within its linear constraints. "I think that sometimes they even can warp the sense of time because they don’t understand time," she says, referencing the film Arrival. She watched her daughter exist in a space where the past and the future were not yet distinct categories. "My experience with my daughter was to see somebody who knew things that hadn't happened yet because she didn’t know the difference between past and future. If you really look at kids, they behave like that. They defy the imposition that we teach them later on because they don't have them yet. Time is something that doesn't exist or apply to them."

This unique innocence of childhood allows for a connection with nature that adults have traded away for a mentality of ownership. Ferrari treats the Earth as a living witness to human failure, linking the exploitation of land directly to the treatment of minorities and women. "That was the center of the movie for me: the connection between what we do to minorities, women, children, and the Earth," she says. "It’s this idea that we own things around us. That we are here, and we own people, we own land, we own everything."

The film draws its morality in color: above ground, the clans move through aggressive, angular shapes colored by hard reds and yellows that Ferrari describes as "potential weapons." Below ground, the world is a soft, blue network of mycelium that represents the internal soul of the planet. When the violence of the clans above ground bleeds into the earth, Ferrari uses the color of their war to inflict visual damage on the soil. The blue roots turn "red and edgy," a symbol of what war does to the soil. She wrote the script in the immediate shadow of the invasion of Ukraine, haunted by the stories her grandparents told her about surviving fascist occupation and concentration camps. "It’s a very scary world. It’s really, really scary, and the thought that we haven’t learned from the past terrifies me," she admits. "The city I come from liberated itself from the Nazis after one of the worst winters. It’s very physically scary."

Despite these cycles of oppression, she finds hope through art and the community of filmmakers she meets on the road. She believes that because the current crisis is so undeniable, people are finally starting to engage at a depth that was missing in her youth. "If I actually think about how it was to be young in the 90s, we are so ahead now," she says. "We have learned so many things as a civilization. In the way we talk about each other, the way we respect women, and the way we respect minorities. I know there's a lot of crap going on, but there's also a lot of very good stuff. I don’t want to forget the good stuff because I’m too scared and only looking at the bad."

Ferrari eventually discovered that her own “strangeness” could be her greatest asset. Working on Song of The Sea she realised that being so close to her young daughter allowed her to animate Saoirse in a very personal way and that was appreciated by the supervisor and the director. “I was actually being valued for something that had been seen as a problem by others before. That’s when I decided I wanted to work again for Cartoon Saloon”

She made Éiru because she remembered being the child adults laughed at. She was right then, and Éiru is right now. The smallest one sees furthest, if we let her. The existence of these stories is her proof that we are not stupid, and that we cannot fall into the trap of believing we are. Engaging with our humanity, whether through art or other people, is the best way to resist the surface-level noise of modern life. "It’s just a matter of getting the hell out of our houses, getting the hell out of our phones, and go meet other people and do stuff together," she concludes. "Life is too short not to do it, and it really gives you hope and very good vibes."